About 4,800,000 people live in Norway, as opposed to almost six million inhabitants of the state of Missouri and more than 300,000,000 residents of the United States.

In terms of surface area, the country is the 67th largest in the world--about 117,484 square miles, compared to Missouri, which is 69,704 square miles. So the population density of Norway is much less than that of the “Show Me” state. And while much of Missouri’s land is used for farming, much of the Norwegian terrain is very inhospitable to agriculture, with thin soil and bare rock. When we’ve gone hiking around Kristiansand, for example, we've noticed that quite a bit of the ground is simply exposed rock dotted with moss and lichens—not the best kind of land for growing crops. Indeed, only a small percentage of the land is farmed. Much of the soil that Norway used to have was scoured away by glaciers during the ice age.

The deep cracks that you see in the western coastline in the above photograph are fjords. Fjords are deep valleys, often with steep walls, that were gouged out of the earth by glaciers during the ice age. Yep, the same glaciers that squeegeed off Norwegian dirt also left deep crevasses along the coast. Courtesy of NASA again, here's a satellite closeup of a fjord--

One would think that Norway, given its northern latitude (Kristiansand, one of the southernmost cities in Norway, is about 58 degrees North, while Boston is 42 degrees North, and Ottawa, the capital of Canada, is about 45 degrees North) would be much colder than it is.

Surprisingly, the coastal city of Bergen, Norway (you can see it on the above map), with a latitude of 60 degrees North, has milder winters than Minneapolis, which is about 44 degrees North. In January, Bergen ranges between an average low of 30.2 degrees Fahrenheit (F) to an average high of 37.4 degrees F, while Minneapolis thermometers register between an average low of 6.8 degrees F and an average high of 21.2 degrees F!

Surprisingly, the coastal city of Bergen, Norway (you can see it on the above map), with a latitude of 60 degrees North, has milder winters than Minneapolis, which is about 44 degrees North. In January, Bergen ranges between an average low of 30.2 degrees Fahrenheit (F) to an average high of 37.4 degrees F, while Minneapolis thermometers register between an average low of 6.8 degrees F and an average high of 21.2 degrees F!

What keeps Norway from turning into a gigantic icicle are ocean and wind currents. It just so happens that there's a giant stream of water that originates in the gulf of Mexico and flows northeast along the eastern coast of the United States and Canada, and then travels east and north across the Atlantic, where it bumps up against the west coast of Europe. This current that flows northeast along the eastern seaboard of the U.S. is known as the Gulf Stream; when the current reaches the eastern coast of Canada and begins to extend out into the Atlantic, it is then known as the North Atlantic Current. So this combined Gulf Stream/North Atlantic Current is a giant conveyor belt transporting liquid heat from the warm and sunny waters off Florida to the western coast of Europe.

And, it also turns out that the wind currents at Norway’s latitude blow from west to east. So, what happens is this:

And, it also turns out that the wind currents at Norway’s latitude blow from west to east. So, what happens is this:

The sun warms the waters in the gulf of Mexico, which carry their heat energy north and west across the Atlantic up to the western coast of Europe, where the water heats the coastline and the air, and where the prevailing winds blow the warm air over Norway (and over much of Europe, for that matter) rescuing Norway (and much the continent of Europe) from what would otherwise be a much chillier winter.

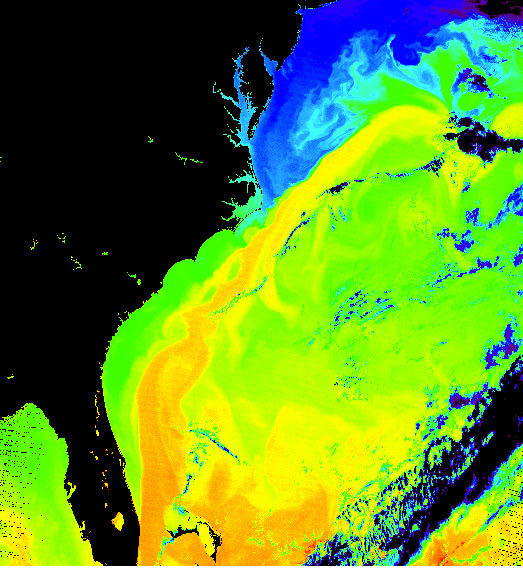

Below is an image of the Gulf Stream as it flows north and east along the Atlantic coast of North America. This image comes from data collected from a NASA satellite, and is what you would call a false-color image--that is, the satellite used its sensors to map out oceanic temperatures, and then someone at NASA assigned colors to represent various water temperatures, with darker colors, such as blue, representing cool water temperatures, and with brighter colors, such as yellow and orange, indicating warm temperatures. The big yellow and orange stripe is the Gulf Stream.

Eventually, much of the warm water represented by that bright stripe will reach Norway.

Nonetheless, despite the warming effect of the Gulf Stream/North Atlantic Current, Norway does get pretty cold in the winter, as the image below, taken by a NASA satellite in February of 2003, shows--and this one is a true-color image--

Below is an image of the Gulf Stream as it flows north and east along the Atlantic coast of North America. This image comes from data collected from a NASA satellite, and is what you would call a false-color image--that is, the satellite used its sensors to map out oceanic temperatures, and then someone at NASA assigned colors to represent various water temperatures, with darker colors, such as blue, representing cool water temperatures, and with brighter colors, such as yellow and orange, indicating warm temperatures. The big yellow and orange stripe is the Gulf Stream.

|

| (From: http://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view_rec.php?id=5248). |

Eventually, much of the warm water represented by that bright stripe will reach Norway.

Nonetheless, despite the warming effect of the Gulf Stream/North Atlantic Current, Norway does get pretty cold in the winter, as the image below, taken by a NASA satellite in February of 2003, shows--and this one is a true-color image--

|

| (From: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=3239) |

|

| (From: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=4605) |

|

| (From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sognefjord,_Norway.jpg) |